Aberdeenshire Gold

Tap o' Noth Caledonian hillfort stands guard over Pictish power center at Rhynie's Barflat in Aberdeenshire

The bard was asked who of the kings of Prydein

is most generous of all

‘And I declared boldly

That it was Owain’

The Gorhoffedd, 12thC Brittonic heroic poem

It has always been our contention that Aberdeenshire gold mined at Rhynie in early-historic times which found its way into Pictish hoards (Traprain Law, Edinburgh) and later melted to form delicate tracery in the Crown Jewels of the King of Scots was one of the major reasons for Rhynie’s importance. After all, a Pictish sub-King who had gold mines on his doorstep and whose pre-Christian ancestors had built no fewer than 10 (Neolithic) stone circles within a radius of as many miles, descended from a great lineage which was responsible for maintaining important sacred traditions. Rhynie’s local mountain, Tap o’ Noth, with its supremely defensive Caledonian triple-ringed hillfort, can be seen for 30 miles in all directions. It is an Aberdeenshire landmark.

Craw Stane, single AD5thC Pictish carved stone left standing at Barflat, ©1856 Stuart drawing 'Symbol Stones of Scotland'

It is gratifying, therefore, (but no surprise) to learn that this summer the Universities of Aberdeen and Chester have found definitive evidence of three fortified enclosures south of the town — a triple power center — in Rhynie’s ‘Royal Mile’ at Barflat, where an unprecedented total of eight Pictish (AD5th-6thCC) carved stones have been unearthed over the years, under the unseeing gaze of Caledonian Tap o’Noth.

It is speculated that the famous — and unique — Roman battle of Mons Graupius (AD83) was fought near here. The foothills of the Grampian mountains’ massif begin within two miles of the outskirts of the town.

A sponsored excavation was finally made possible this year after investigations begun in 2007 by Rhynie Environs Archaeological Project (REAP), in a collaboration between the two universities’ archaeological departments, led by Dr Gordon Noble (UA) and Dr Meggen Gondek (UC). Their interest was piqued by positive resistivity surveys taken in 2005 and 2006, but they were unable to raise sufficient backing to begin. They have discovered three giant enclosures standing close together, one of them a ‘Peel’, surrounded by a massive pallisaded wooden structure of spiked tree-trunks: the ultimate impenetrable fence.

2011 excavation by REAP uncovers large fortified Pictish Power Center at Rhynie. Famous Craw Stane marks south flank of a ceremonial entrance on the East of the pallisade

Dr Gondek said: “Some of the material culture we uncovered is exceptional. It is one of the most significant finds of early medieval imported goods in north Britain.”

Finds include part of a Roman amphora — a large pottery vessel from the eastern Mediterranean used to hold wine or oil; a pair of amber ear-drops — clearly high-status objects — bronze pins, a fragment of 6thC blue glass drinking bowl, Roman pottery and other drinking vessels — all indicating strong links with other cultures well beyond the shores of mainland Britain.

Because these artefacts could be dated to the AD5-6thCC, this implies that the Pictish chieftains/sub-Kings –whose stronghold this was– were powerful enough to have a flourishing trade route direct to Rome and the Mediterranean.It has been speculated many times before on prehistoric sites such as this that the Caledonian (Iron Age) fortress on Tap o’ Noth is itself named for an important prehistoric chieftain called Nocht. Etymology of the name is not a misspelling derived from the wind direction! Tap o’Noth overlooks a remarkably dense cluster of ancient sacred sites (Nether Wheedlemont, Upper Ord, Mill of Noth, Clatt, Percylieu to name a few) rivalling the Wiltshire heartland and Salisbury Plain. It has maintained anonymity because of its remote location in western Aberdeenshire, where high mountain routes to the grouse moors and Grampian hills are regularly cut off in winter.

This remote status may be about to change.

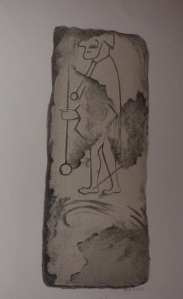

Rhynie Man, a six-foot Pictish caricature from the 6thC dug up in a field in 1978. It is presently housed in Council HQ, Aberdeen, but a Rhynie initiative to have it returned is underway

Even when the then farmer at Barflat, Gavin Alston, demanded ‘treasure trove’ payment from Grampian Regional Council (Archaeology) in 1978 in exchange for his freshly ploughed-up Pictish ‘Rhynie Man’ (presently housed in Aberdeenshire Council’s HQ at Woodhill House, Aberdeen), right, there was no follow-up to discover why so many Pictish stones had surfaced in a single 30-acre field. Now his son Kevin Alston crows: “This will put Rhynie on the Map.”

While the excavation revealed a number of structures and foundations associated with buildings at a shallow depth below the ploughing level, the relatively undisturbed context of both jewellery and drinking vessels imply a stronghold, even a ‘palacio’ which was more common in the 6-7-8thC Pictish capital of Forteviot in Strathearn. This is exciting because the Rhynie artefacts were found within the remains of what would have been an elaborate system of defensive enclosures, including two deep ditches and a massive timber palisade — alongside remains of extensive wooden structures and fortified buildings. Early power centres of the Picts are scantily documented. The Pictish Chronicle, whose Latin original is lost, and whose various 12thC copies have been ‘tampered with’ by Scots successors to Pictish wealth and culture, gives much detail of names and historic events, particularly in AD7-8thC. But Scots addenda and manipulation of text and some names has traditionally made historians unwilling to depend on it. The Rhynie revelation provides an exciting opportunity to find out more about how the kingdoms of powerful Pictish warlords were consolidated in the North.

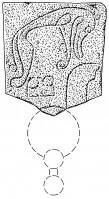

Another of the 8 Pictish symbol stones found at Rhynie-Barflat; a fragment stands in the pre-Reformation kirkyard showiing (royal) dolphin, part of sword, top of mirror-comb symbolizing matrilineal succession, drawing courtesy RCAHMS

Predecessor to Rhynie Man: ceremonial stone figure, Barflat#4, currently in the town's Market square

Pictish kings and sub-kings ruled a nation which grew from a loose confederation of tribal groups in the third century to become a major political and land-owning force at the time of their takeover by the Scots in the ninth

It is anticipated that further excavations in future years at Rhynie will prove this case conclusively. We welcome all results from the REAP project and also applaud the Rhynie community in its initiative to bring back to their own doorstep those Pictish stones and relics which were previoiusly removed without their permission.

Bravo.

©2011 MCYoungblood/Derilea/Devorguila